Catechol-O-Methyltransferase (COMT) is one of the several enzymes that degrade dopamine, epinephrine, and norepinephrine. COMT breaks down dopamine mostly in the part of the brain responsible for higher cognitive or executive function (prefrontal cortex).

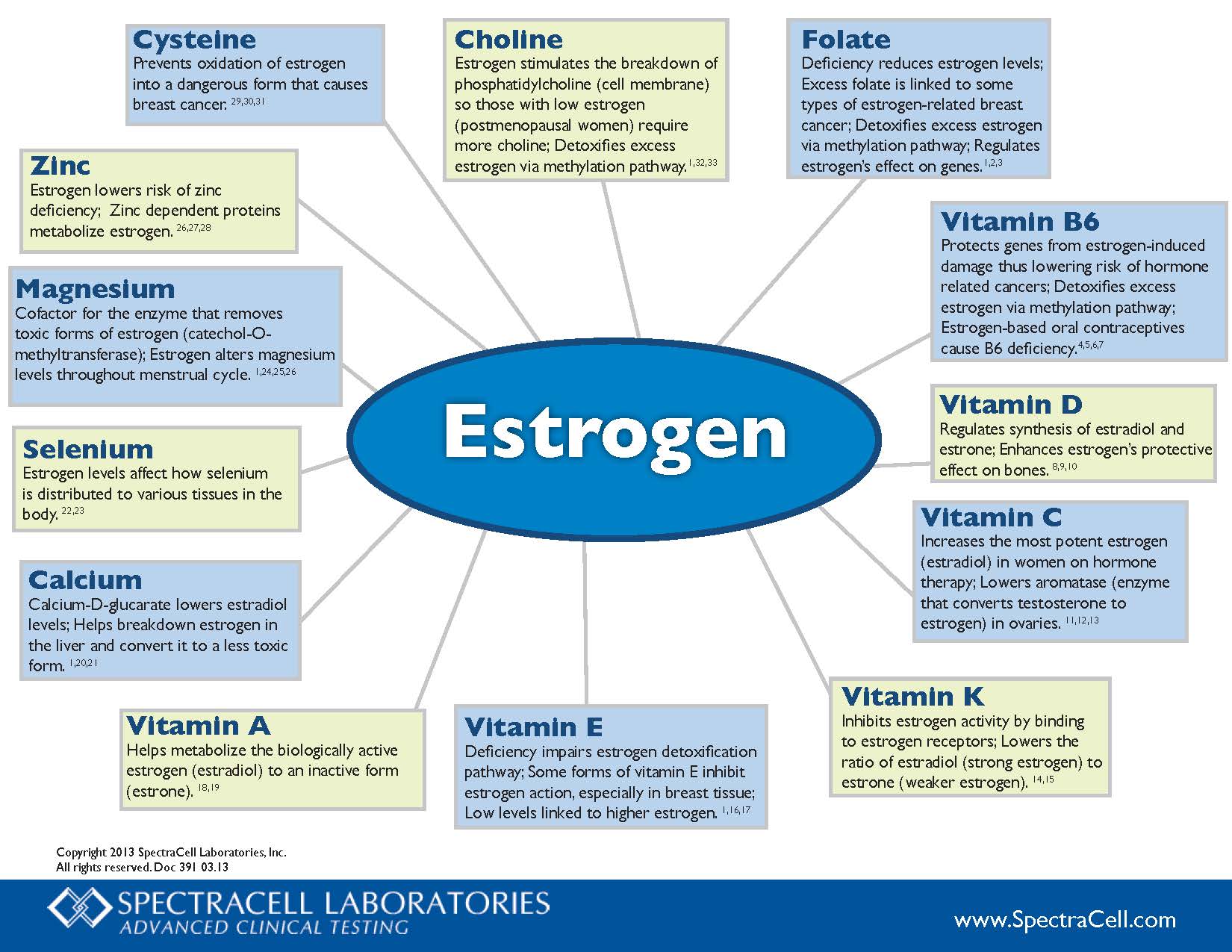

COMT helps break down estrogen byproducts that have the potential to cause DNA mutations and cause cancer.

If you have higher COMT levels:

- Mucuna to increase dopamine,

- Tyrosine to increase dopamine,

- EGCG/Tea (COMT inhibitor),

- Epicatechins/Chocolate (COMT inhibitor),

- Luteolin

If you have lower levels of COMT, the following may counteract some of the effects of the gene:

- SAM-e – however, this can increase dopamine levels in people who already have high dopamine.

- Methyl Guard Plus to ensure adequate B6, B12, folate and betaine to support the formation of S-adenosylmethionine and prevent elevated homocysteine; S-adenosylhomocysteine inhibits COMT activity.

- Ensure adequate anti-oxidants to prevent oxidation of dopamine and pro-carcinogenic 4-hydroxyestrogens,

- Magnesium Citrate (magnesium is a cofactor)

- Be careful of the following supplements that are the targets of COMT: quercetin, rutin, luteolin, EGCG, catechins, Epicatechins, Fisetin, Ferulic acid, Hydroxytyrosol

- Avoid excessive alcohol consumption. Since alcohol-induced euphoria is associated with the rapid release of dopamine in limbic areas, low activity COMT variant would have a relatively low dopamine inactivation rate, and therefore would be more vulnerable to the development of alcohol dependence.

- Avoid stimulants, especially amphetamines. Amphetamines may do worse with people who are AA, but later studies did not replicate this. It could be differences in study design.

- Avoid chronic stress (stress hormones require COMT for degradation and compete with estrogens),

Catechol Estrogens, Cancer and Autoimmunity

Catechol estrogens form from CYP enzymes breaking down Estradiol and Estrones. Catechol estrogens can break DNA and cause cancer and autoimmune conditions. COMT methylates (using SAM) and inactivates these catechol estrogens (2- and 4-hydroxycatechols). The products of COMT methylation are 2- and 4-o-methylethers, which are less harmful and excreted in the urine (they have anti-estrogen properties). However, if COMT is inhibited too much either because of genetics or dietary inhibition, it should result in higher levels of catechol estrogens, especially if glucuronidation and sulphation pathways are not working. 4-Hydroxyestrone/estradiol was found to be carcinogenic in the male Syrian golden hamster kidney tumour model, whereas 2-hydroxylated metabolites were without activity. 4-Hydroxyestrogen can be oxidized to quinone intermediates that react with purine base of DNA, resulting in depurination adduct that generates cancerous mutations. Quinones derived from 2-hydroxyestrogens are less toxic to our DNA. Estrone and estradiol are oxidized to a lesser amount to 2-hydroxycatechols by CYP3A4 in the liver and by CYP1A in extrahepatic tissues or to 4-hydroxycatechols by CYP1B1 in extrahepatic sites, with the 2-hydroxycatechol being formed to a larger extent .

It has been observed that tissue concentration of 4-hydroxyestradiol is highest in malignant cancer tissue, out of all the estrogens. The concentration of these Catechol Estrogens in the hypothalamus and pituitary are at least ten times higher than parent estrogens. Catechol Estrogens have potent endocrine effects and play an important role in hormonal regulation (those produced by hypothalamus and pituitary).

Increased availability of estrogen and estradiol for binding and hypothalamic sites would facilitate the formation of Catechol Estrogens. These estrogens affect Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and maybe follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and prolactin. Catecholestradiol competes with estradiol for estrogen binding sites in the anterior pituitary gland and hypothalamus and dopamine binding sites on anterior pituitary membranes.

Other possible mechanisms of inactivation of these catechol estrogens include conjugation by glucuronidation and sulphation. High concentration of 4-hydroxylated metabolites caused insufficient production of methyl, glucuronide or sulfate conjugate which in turn results in catechol estrogen toxicity in cells and oxidation to semiquinone and quinone, which may reduce glutathione (GSH). These oxidation products could lead to DNA mutations. The quinone/semiquinone redox system produces superoxide ions (O2¯ ) which can react with NO to form peroxynitrite, which could cause DNA damage. In summary, CEs lead to the production of potent ROS, capable of causing DNA damage, thus playing an important role not only in causing cancer but also in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and Rheumatoid Arthritis. The abilities of the estrogens to induce DNA mutations were ranked as follows: 4-hydroxyestrone (most damaging) > 2-hydroxyestrone > 4-hydroxyestradiol >2-hydroxyestradiol > > Estradiol, Estrone.