Abstract

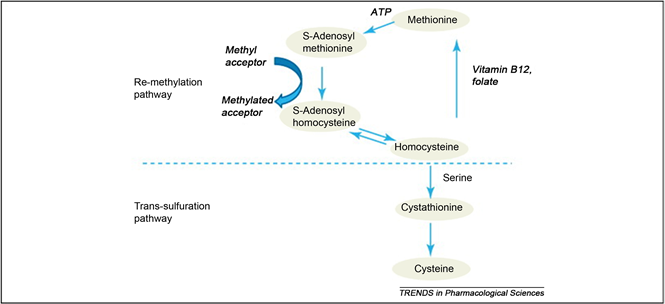

Homocysteine is an intermediate substance formed during the breakdown of the amino acid methionine and may undergo remethylation to methionine or trans-sulfuration to cystathionine or cysteine. The metabolism occurs via two pathways: remethylation to methionine, which requires folate and vitamin B12; and transsulfuration to cystathionine, which requires pyridoxal-5’-phosphate.

The disturbances in the metabolic pathways lead to the accumulation of Hcy, either by insufficient transsulfuration (through CBS mutations or vitamin B6 deficiency) or by a blockage of remethylation. In the latter case, folate or vitamin B12 deficiency may be involved, as well as MTHFR.

High levels of Hcy induce sustained injury of arterial endothelial cells, proliferation of arterial smooth muscle cells and enhance activity of key participants in vascular inflammation, atherogenesis, and vulnerability of the established atherosclerotic plaque.

Hyperhomocysteinemia has become the topic of interest in recent years. It has been highly associated with increased risk for cardiovascular disorders, such as, atherosclerosis, thromboembolism and dyslipidemia.

Women with PCOS show constellation of metabolic syndromes. Obesity, hyperandrogenemia and type 2 diabetes mellitus is the hallmark of PCOS which later becomes the risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Various studies had revealed the presence of increased Hcy level in PCOS women which may or may not be associated with other biochemical parameters. Intense treatment for PCOS can influence homocysteine levels.

Introduction

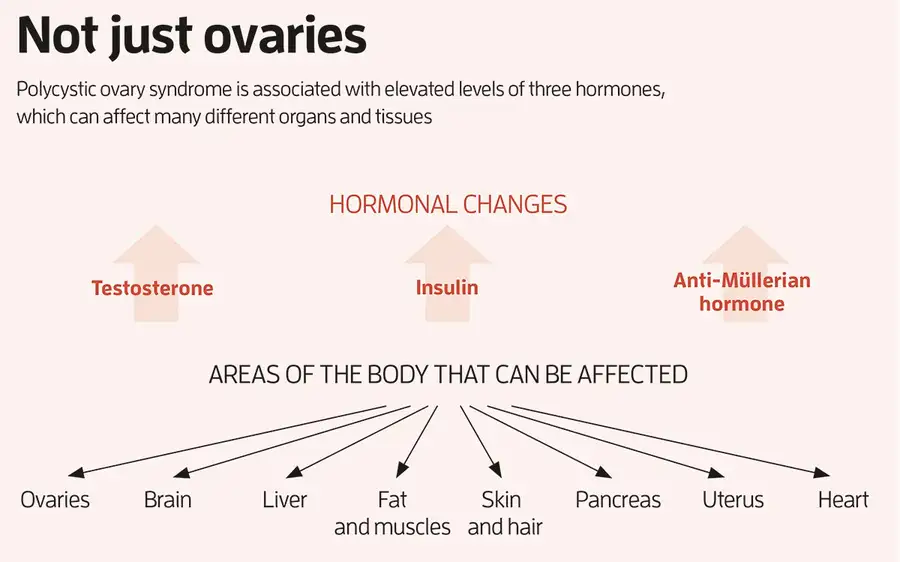

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) proves as the most common endocrine disorder with a prevalence of 5% to 15% worldwide [1] , for the women of active reproductive age, but the prevalent rate varies depending on the criteria used for the diagnosis [2] [3] . According to the Rotterdam diagnostic criteria, the prevalence rate of PCOS accounts up to 18% of reproductive-aged women [2] [3] , whilst the prevalence rate is 10% when using NIH criteria for diagnosis criteria [3] but the prevalence is still unknown in children [2] [4] . Three different criteria have been implemented for the diagnosis of PCOS: the NIH criteria (1990), the Rotterdam criteria (2003) and the Androgen and PCOS society (AE-PCOS) criteria (2006) [5] [6] . Amongst the three criteria, the Rotterdam criterion was adopted as the Practice Guidelines of the Endocrine Society [2] [7] . The Rotterdam criteria comprise features as, chronic menstrual dysfunction, clinical or biochemical hyperandrogenism and polycystic ovaries confirmed by ultrasonography (≥10 follicles and ≥10 ml ovarian volume) [8] . The etiology of PCOS still remains unclear but various predisposing genes interfere with environmental and lifestyle manners [5] [9] , makes PCOS a complex genetic disorder. The constellations of symptoms significantly affect the quality of life of PCOS women and the syndrome is associated with an increased long term risk factors such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, infertility, cancer and psychological disorders [10] .

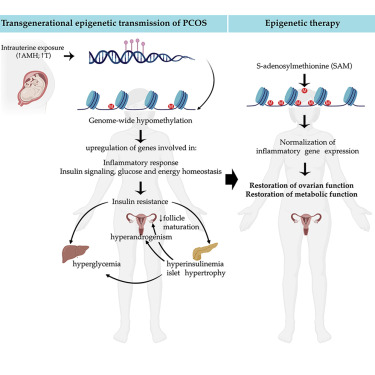

In current years, homocysteine, a biosynthesis of methionine has proved as a major cardinal feature of PCOS. It is a non-protein a-amino acid and cysteine homologue. Its metabolic pathway encompasses either remethylation to methionine or through transsulfuration to cystathionine as shown in Figure 1 [11] . The first metabolism pathway requires folate and vitamin B12 whereas the latter requires pyridoxal-5’-phosphate. S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) augments the synthesis of both pathways which is a moderator of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) and inhibitor of cystathionine β-synthase (CBS). The metabolic pathways are interrupted by any impaired function either by insufficient transsulfuration through CBS mutation or deficiency of vitamin B6 or secondly by remethylation blockage, can lead to abnormal accumulation of plasma Hcy. In the latter case, the accumulation of homocysteine could be due to deficiency of folate or vitamin B12, as well as MTHFR [12] .

A condition that emerges from disrupted homocysteine metabolism is hyperhomocysteinemia which has been known as the most significant risk factor for cardiovascular disease and has been confirmed by recently conducted meta-analysis study by Homocysteine Studies Collaboration [13] . Deficiencies in cystathionine beta synthase, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase or enzymes involving methyl-B12 synthesis, as a result of a rare genetic defect, lead to severe hyperhomocysteinemia. In fasting status, due to mild impairment in the methylation mechanism (i.e. folate or B12 deficiencies or MTHFR thermolability), occurs mild hyperhomocysteinemia [12] . Homocysteine play a role as a mediator for endothelial damage and dysfunction [14] that subsequently impairs endothelial vasoreactivity and decrease endothelium thromboresistance. Hence, hyperhomocysteinemia associated with increased risk of atherosclerosis, thromoboembolic diseases and hyperinsulinemia is verified which is directly proportionate to increased risk of cardiovascular disorders with a strong correlation to insulin resistance. Hyperhomocysteinemia also aggravates the incidence of late pregnancy complications, such as preeclampsia, abruption placentae, preterm birth and intrauterine fetal death [15] . Hyperhomocysteinemia is also one of the major factors that leads to early miscarriages by impairing by interfering endometrial blood flow and vascular integrity [16] and also described as the sole variable resulting in recurrent pregnancy loss [17] .

According to numerous clinical studies, PCOS in women is associated with existence of endothelial and platelet dysfunction, minimal chronic inflammation, increased coronary artery calcification and carotid intima-media thickness in PCOS women [18] . PCOS women are highly susceptible to both cardiovascular risk factors, such as, obesity dyslipidemia, hypertension and type-2 diabetes mellitus, and mood disorders, such as depression and anxiety [2] .

Influence on Hcy Level Post PCOS Therapy

Insulin and Hcy have the ability to induce each other by inhibiting hepatic CBS [23] that results in hyperhomocysteinemia leading to compensatory hyperinsulinemia by inducing insulin resistance. This may impair activity of the MTHFR or CBS enzymes, leading to abnormal deposition of homocysteine in plasma [24] [51] [52] . This explains that insulin resistance may be the most important marker of metabolic disease in PCOS women [53] . Hence, metformin has always been the mainstay treatment for PCOS women with insulin resistance. With administration of metformin, some study has shown beneficial decrease in plasma Hcy level [8] [54] . Nonetheless, it is also studied that metformin monotherapy is unsatisfactory [55] . The study conducted by Vrbrikova et al. revealed that the treatment with metformin only may increase the plasma Hcy level [56] . Administration with rosiglitazone and metformin seem to decrease elevated oxidative stress compared to metformin treatment but no significant changes were observed in plasma Hcy [40] . Kilicdag et al. also reported the same result [57] . This statement can be explained by folate depletion and malabsorption of vitamin B12 [58] [59] that disturbs Hcy metabolism, thus, supplementation with folate can be preventative [57] [60] . Moreover, treatment with metformin and cyclic medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) also tend to increase Hcy level [55] . Stefano Palombo et al. reported that treatment with metformin can slightly reduce the Hcy level in PCOS women, but supplementation with folate has shown to increase the beneficial effect [60] . Hence, folate supplementation is the first therapeutic measure advised in obese PCOS patients that prevents rise in Hcy level during weight loss. A prospective randomized clinical study in 2010, in both obese and non-obese PCOS women, observed dramatic decrease in plasma Hcy level when treated with metformin. However, the study in the both group when treated with oral contraceptives increased the plasma Hcy level and other biochemical parameters that increased the metabolic risk [61] .

Statins have also been administered and seems to deplete serum Hcy levels in PCOS [48] [62] . In a prospective cohort study, the combination of ethinyl estradiol/drospirenone (EE-DRSP) and spironolactone treatment were given to lean and glucose tolerant patients with PCOS for 6 months, improved androgen excess but the combination increased Hcy level and CRP level [63] . Similarly, oral contraceptives containing 0.03 mg ethinyl estradiol and 0.15 mg desogestrel for 6 months had significantly decreased Hcy level in non-obese normoandrogenic PCOS patients [61] . Furthermore, oral contraceptives containing 35 µg ethinyl estradiol and 2 mg cyproterone acetate had resulted in rapid decrease in Hcy level in non-smoking PCOS women [64] [65] [66] , whereas Hcy level remains high in the smokers. It has also been studied that Hcy levels decreased after regular exercises for 6 months [67] and also have shown to decrease 3 months after ovarian surgery [68] .