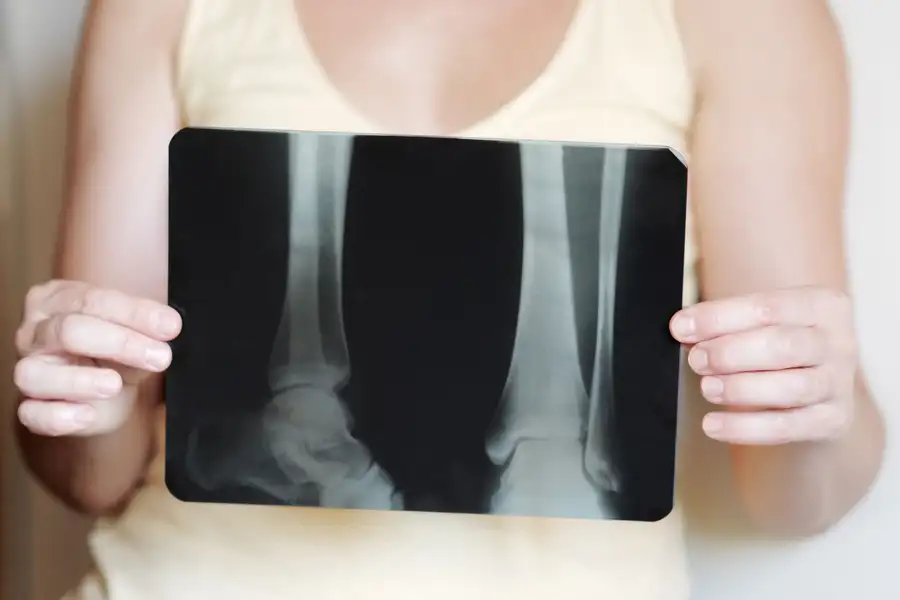

If you look in the mirror and see new wrinkles forming, you likely blame aging skin. But emerging wrinkles may actually be signalling diminishing bone density. It turns out osteoporosis and skin crepiness share some surprising connections.

Several studies reveal that women with osteoporosis and osteopenia tend to have more pronounced wrinkling and other signs of skin aging compared to their peers with normal bone density. Why does low bone mass translate to wrinkly skin? A few reasons explain this link:

- Collagen loss – the collagen matrix that keeps skin plump and smooth is the same collagen that maintains the skin plump and prevents wrinkling.

- Hormone changes – oestrogen decline during menopause can accelerates bone loss and decreases collagen and skin thickness. This contributes to sagging and wrinkling.

Studies show that skin and bones share common building blocks-proteins, and aging is accompanied by changes in skin and deterioration of bone quantity and quality. Deepening and worsening skin wrinkles are related to lower bone density – the worse the wrinkles, the lesser the bone density, and this relationship is independent of age or of factors known to influence bone mass.

Your wrinkles are trying to tell you to take care of your bones! Don’t dismiss these visible clues your body provides. Boosting bone density through having collagen daily, including weight-bearing exercise, nutrition, and other interventions can renew skin thickness and hydration.