Today, a PCOS diagnosis is based on having two of three characteristic features. The first is high levels of male sex hormones like testosterone, which can cause acne, excess hair on the face and body and thinning head hair. The second is irregular or no periods, which occur because eggs often haven’t developed properly in the ovaries. This prevents their regular monthly release in the form of ovulation, meaning that it can take longer to become pregnant. The third is the presence of 20 or more “cysts” on either ovary, which are now understood to be eggs that are stuck in an immature state, rather than actual cysts.

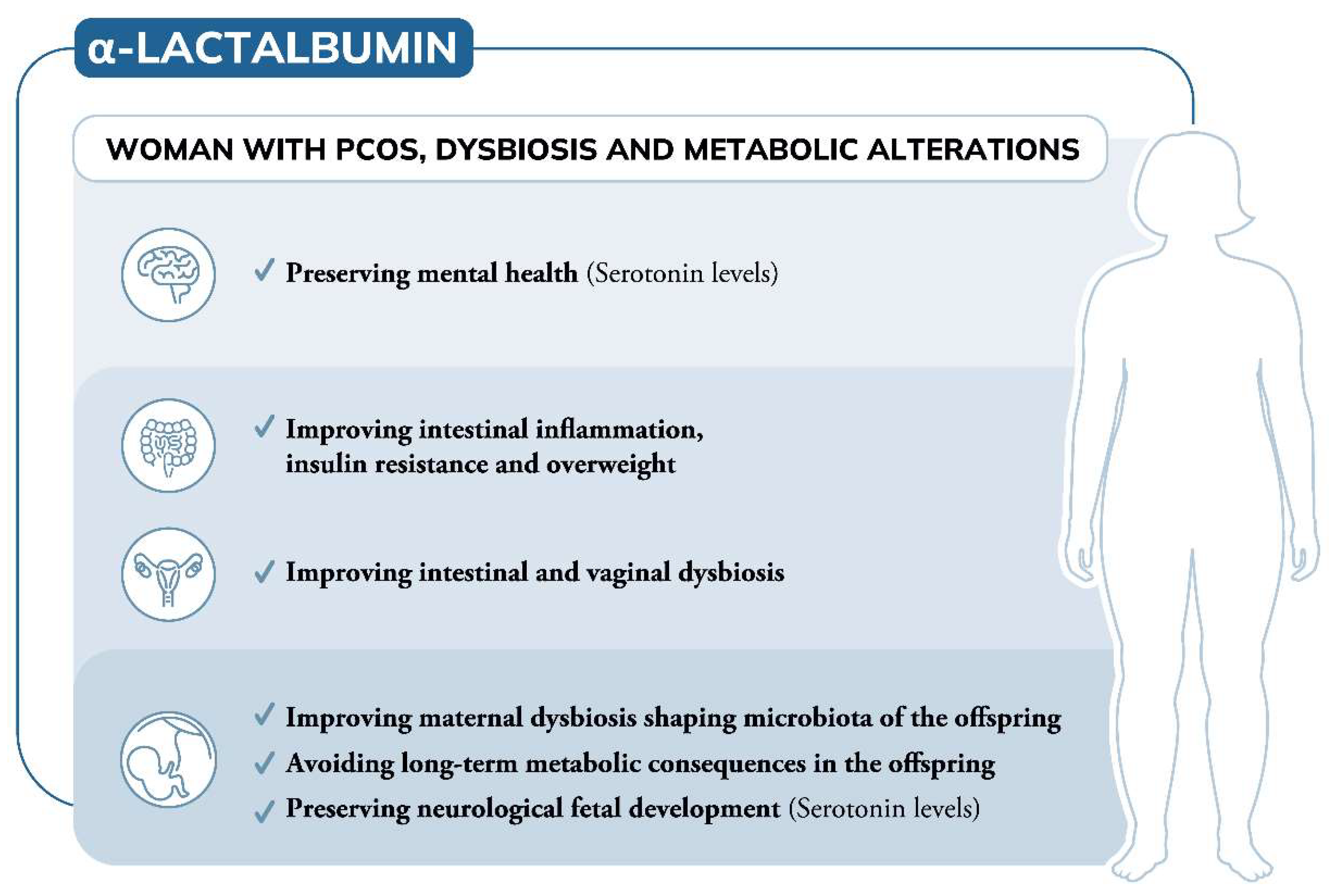

In addition to these key features, around 50 to 70 per cent of individuals with PCOS develop resistance to insulin, which can lead to higher levels of this hormone, type 2 diabetes, weight gain, high blood pressure and heart disease. PCOS also increases the risk of endometrial and pancreatic cancer, and can cause anxiety, depression and reduced sex drive in some people.

The psychological effects may be directly caused by hormonal imbalances. Alternatively, they might arise because “if you’re a teenager, when PCOS symptoms emerge, and you’re gaining weight rapidly, you have significant acne, your periods are all over the place and you have body hair where you don’t want it, it can have a really significant impact on your self-esteem”, says Helena Teede at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia.

Finally, people with PCOS who become pregnant are more likely to have miscarriages or complications like gestational diabetes or preterm birth.

PCOS affects around 5 to 18 per cent of cis women and up to 58 per cent of trans men, although the reason why this latter figure is higher has yet to be pinned down. Despite being relatively common, it has long been one of the most neglected health conditions, says Teede. “It’s twice as common as diabetes but gets less than a hundredth of the funding,” she says. Elisabet Stener-Victorin at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden tells a similar story. “Up until about 10 years ago, I would never put ‘PCOS’ in the title of my research grant applications because it really dragged down my chances of getting funding,” she says.

Part of the problem is that it is “everybody’s business and nobody’s business”, says Teede. The many symptoms of PCOS, which vary widely between individuals, means it is managed by a range of health professionals: endocrinologists, gynaecologists, reproductive specialists, dermatologists, primary care doctors, dieticians and so on. For a long time, no one was sure who should be steering the ship and each speciality treated PCOS differently, which “constantly created confusing messages”, says Teede.

To rectify this, Teede led the development of the first international, evidence-based guidelines for PCOS, which were published in 2018. They were based on consultations with more than 3000 health professionals and people with the condition from 71 countries.

The guidelines explain how to diagnose PCOS and manage it using existing treatments. Diet and exercise interventions are recommended to begin with, since these have been shown to simultaneously improve the metabolic, reproductive and psychological features of the condition. This is because diet and exercise can assist weight loss and improve blood sugar control, which, in turn, reduce insulin and testosterone levels.

Stener-Victorin and her colleagues, found that women in Sweden were five times as likely to be diagnosed with PCOS if their mother has the condition. No single gene has been found to be responsible for PCOS, but certain patterns of genes involved in testosterone production, ovarian function and metabolism appear to be linked with the condition. Still, these genetic variations don’t tell the whole story of how PCOS is passed down generations.

Growing evidence suggests PCOS-related hormonal imbalances during pregnancy can also have an effect on the fetus. “In a woman with PCOS, you have both the genetic factors and the in utero environment,” says Stener-Victorin. “I think it’s likely that you may carry some susceptibility genes and then you have an in utero environment that triggers its onset.” Two hormones suspected to be involved in this in utero effect are testosterone and anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), both of which tend to be elevated in those with PCOS.

Stener-Victorin and her colleagues have found that injecting excess amounts of a form of testosterone into pregnant female mice caused their female offspring to develop many of the hallmarks of human PCOS, including irregular cycles, and greater fat mass and body weight. Similarly, when Giacobini’s team injected excess AMH into pregnant female mice, their female offspring had irregular cycles, the appearance of “polycystic” ovaries, elevated testosterone, insulin resistance, higher body weight and greater fat mass. “We now have an animal model that not only recapitulates the reproductive aspects of PCOS, but also the metabolic component seen in many women,” says Giacobini. “So, we can use these animals to really investigate the disease and design new treatment options.”

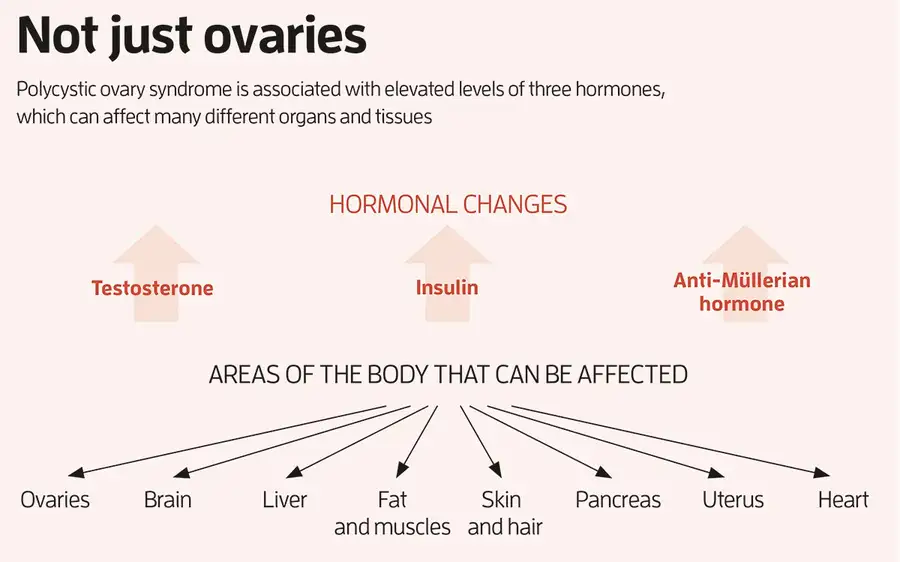

Most recently, his team discovered that the daughter mice with PCOS-like symptoms, whose mothers were injected with excess AMH during pregnancy, had altered expression of several genes involved in inflammation. This has led Giacobini to believe that PCOS is actually an inflammatory condition. His team found increased expression of inflammatory genes in the brain, ovaries, liver and fat of the mice, which he says may explain why these organs are all affected by the condition (see “Not just ovaries”, pictured above). This fits with emerging evidence of a link between inflammation and PCOS in people. A 2021 analysis led by Saad Amer at the University of Nottingham, UK, for instance, found that women with PCOS had significantly higher levels of an inflammatory marker called C-reactive protein compared with those without the condition.

Could these findings lead to new treatments? Giacobini’s team has spent the past few years developing drugs to lower AMH levels. The researchers are about to test these in mice, before hopefully progressing to human trials. “But we need to be very cautious because there are AMH receptors in different parts of the brain and a range of organs,” he says. “We cannot predict yet whether such treatment may trigger undesirable side effects until we fully comprehend the role of AMH in all those organs.” Interestingly, AMH declines with age, which may explain why some with PCOS who were unable to conceive naturally in their 20s and 30s are able to do so in their 40s, when their AMH levels fall into the normal fertility range, says Giacobini. This delayed fertility window could also be the reason why those with PCOS reach menopause four years later than average.

Another treatment option may be drugs that correct the altered expression of inflammatory and other genes implicated in PCOS, says Giacobini. Last year, his team showed that PCOS-like symptoms could be reversed in female mice by giving them a drug called S-adenosylmethionine that corrected the altered gene expressions. This drug couldn’t be safely given to people because it affects too many other genes, but it may be possible to develop more tailored treatments in the future, says Giacobini.

Teede says these approaches are worth pursuing, but cautions against extrapolating too far from animal studies. “PCOS is not caused by one mechanism, it’s multiple mechanisms that add up together,” she says. “If you’ve got an animal model that uses one mechanism to induce a PCOS-like status, you might be able to reverse that one mechanism, but treating a complex multifactorial condition in humans is harder.”

Misleading moniker

Is it time to rename polycystic ovary syndrome? There is a growing push to do so since it is now recognised as a whole-body condition, people can be diagnosed with it even if they don’t have “polycystic” ovaries and we now know that the “cysts” are undeveloped eggs, not actual cysts.

“We desperately need a name change,” says Helena Teede at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia. “The name should reflect what it actually is. Having a name around the ovaries misses the diversity of the condition.”

Teede and her colleagues are consulting health professionals and people with the condition to agree on a new name – the most preferred one at this stage is “reproductive metabolic syndrome”.

They hope to formalise this name change in the middle of this year when they release an updated version of the international guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of the condition.